|

|

| Building the foundation for juvenile justice |

| By Patrick M. Sullivan, FAIA |

| Published: 03/19/2007 |

For more than 2,000 years western civilization shamefully neglected the children of our society. They were abandoned throughout Europe from Hellenistic antiquity to the end of the middle ages. Parents deserted their offspring in desperation when they were unable to support them due to poverty or disaster, or were unwilling to keep them because of physical condition, ancestry, religious beliefs, self interest, or interest of another child.

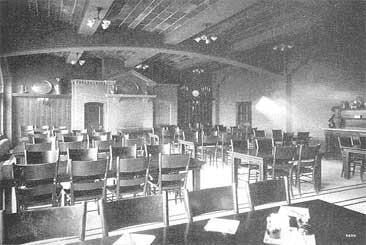

For more than 2,000 years western civilization shamefully neglected the children of our society. They were abandoned throughout Europe from Hellenistic antiquity to the end of the middle ages. Parents deserted their offspring in desperation when they were unable to support them due to poverty or disaster, or were unwilling to keep them because of physical condition, ancestry, religious beliefs, self interest, or interest of another child.At no point did European society entertain serious sanctions against abandonment; most ethical systems either tolerated or regulated desertion. The English Poor Laws, beginning with the Statute of Laborers in 1349, began regulating the working and nonworking poor, and in 1536 provided an act that states “Children less than fourteen years of age and above five that live in idleness, and be taken begging may be put to service - to husbandry, or other crafts or labours.” In 1601, primary family responsibility was added to the English Poor Laws and local authorities were empowered to build housing for the impotent and poor. If it was found that a child's parents were unable to care for the, the child could be taken away and made an apprentice. Eventually abandoned and neglected children became the responsibility of the monarch, and the Commonwealth became their guardian. The “Parens Patriae,” doctrine meaning “father of the country,” gave courts the right to act in place of the parent and recognized the monarch as the overall father figure (the godfather) of all the populace. This established societal patterns that left children with few personal rights. The ideas of the European courts and customs, especially the English Poor Laws, set the practices for subsequent social legislation and regulation of the working poor in Colonial America. (They may even be compared with the health, safety, and welfare system in America today.) In England, society's attitude toward delinquent children began to change in 1788. The Philanthropic Society of London, under the influence of John Howard(1), established an “asylum,” a place of safety for delinquent boys. Another group, the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Offenders, established a similar, separate refuge in 1816, and a public institution for juvenile delinquents was opened near Birmingham in 1817. Early American Reform In America similar concerns about housing delinquent and abandoned children led to the separation of juveniles and adults. In 1817, the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism was formed in New York City. In its 1822 paper, “The Penitentiary System in the United States,” the society argued that there was a necessity to provide new and separate prisons for juveniles. However, the prisons were to be operated as schools for instruction rather than punishment. Vocational training and reformation was stressed. The first American publicly funded and legally chartered custodial institution for juvenile offenders, the “House of Refuge,” was established in New York City in 1824. In Philadelphia similar institutions followed in 1860. The first houses were multi-story, grim, prison-like institutions. During the mid-1800s the almshouse and workhouse practices evolved into the training school, reformatory, truant school or school of industry. The concept of the congregate living and working situation was used as a means of training the abandoned or delinquent juvenile. The reform school system was introduced in Westborough, Massachusetts, at the Lyman Reform School for Boys, in 1846, and at the Reform School for Boys in Lancaster, Ohio, in 1858. The treatment philosophy of these institutions recognized that juveniles were more likely to be rehabilitated than adults and, therefore, should not be treated within adult institutions.  Lyman Reform School for Boys Westborough, Massachusetts The Lyman School was almost self-sufficient. Youth raised livestock, grew vegetables, sewed their own clothes and built many of the facilities located on the school grounds. These facilities were the models for the Colorado's Mount View Campus in 1881 and Washington's Greenhill School in 1886.  Green Hill School, 1900 Chehalis, Washington Reform Movements Despite the increased use of reformatories or training schools, the notion of punishment rather than reform was difficult to abolish. In the decade of the 1880s(2), the nation experienced a 50 percent increase in the number of prison inmates. Child offenders constituted one-fifth of the prison population, both adult and juvenile. Confinement conditions prevalent at the time, disease, squalor, and overcrowded living areas, led to public concern and initiated a series of reform movements. Advocates during the 1890s, referred to as the “child savers,” emphasized the need for prevention and opposed the conditions of the reform schools. They founded children's aid societies to distribute food and clothing, and to provide temporary shelter and employment for destitute youths. Urban youngsters were placed in apprenticeships with farm families in the West and Midwest. A similar movement in Chicago was organized by a group of feminist reformers who passed special laws for juveniles and created institutions for their care and protection. Louise de Koven Bowen and Jane Addams were civic-minded philanthropists who transformed child saving from a respectable hobby into a passionate commitment. Bowen's primary interest was the protection and welfare of children. She attributed the rise of youthful crime to the corrupting influences of city life, where dirt, crowding, artificiality, and impersonality robbed children of their innocence. Playgrounds, supervised recreation, “morals police,” kindergartens, visits to the country, stricter laws, and more efficient law enforcement were her solutions to delinquency. The problem of juvenile crime, said Bowen, would be diminished by stringent enforcement of laws and the development of resolute character in youth. Addams was the epitome of professional philanthropy. Her full-time career was centered on youth and family reform interests. After college graduation, she encountered the concept of a settlement house at Toynbee Hall in London and observed educated university graduates living and providing social services in the neighborhood community.  Hull House Butler Building Chicago, Illinois In 1889 with Ellen Gates Starr, Addams established Hull House. The settlement house was located at the corner of Polk and Halsted streets in Chicago. The neighborhood was a slum with overcrowded tenements, crime, inadequate schools, inferior hospitals and insufficient sanitation. Hull House workers organized clubs, recreation, and educational programs for people in the neighborhood. The distinguishing characteristic of the settlement house was its ability to deliver services without employing professional social workers or welfare agency staff. Social and welfare workers of the time had developed a reputation for being judgmental and punitive. Contemporary delinquency control and prevention programs can be traced to the reforms of the child savers at the end of the nineteenth century. Socially responsible citizens created special judicial and correctional institutions for the identification and management of troubled youth. The origins of the definition of the juvenile as a delinquent are found in the programs and ideas promulgated by these social reformers. This era of public responsibility was the next step in the evolution of social reform and welfare programs in America(3).  Hull House Coffee Room Chicago, Illinois Juvenile Courts In 1899, the Chicago Bar Association supported a statue which established a separate and distinct legal process for mistreated or delinquent juveniles. The concept followed the Parens Patriae principles and appointed the juvenile court as the representative of the state acting in lieu of the parent and in the best interest of the child. Cottage Institutions The origins of the family plan can be traced back to the Rauhe Haus, founded in 1833 by Dr. Johann Heinrich Wichern near Hamburg. The separate residential cottage plan was also introduced by the French penal reformer, Frederic Auguste Demetz. The French youth campus was opened in 1840 at Mettray. The cottages were three-story structures, with ground floor workshops. Like the early Pennsylvania prisoner reformers, Demetz believed in the influence of hard work. He also was enlightened enough to set up a form of self-government for the detainees. The concept or model of self government was instituted in the early 1900s at the George Junior Republic in Freeville, which is near Ithaca, New York. The institution organized the treatment to be a virtual microcosm of the outside world, and self-government meant that youths were involved in the definition and enforcement of rules under the close supervision of staff. This concept is still fundamental in treatment methods known as guided group interaction or positive peer culture. House Parents Cottage parents were to provide the paternal supervision, understanding, and counsel that were missing in the youth's home life. The system exists today at Girls and Boys Town in Nebraska, Le Roy Boys Home in California, The David and Margaret Home in California, and other small, private programs. Early programs were positive. A surrogate family was better than no family. Today labor laws require a hybrid structure. Statutes limit the weekly work period to 40 or 48 hours per employee. Therefore house parents cannot be “at home” except for normal working hours. Their presence has to be supplemented by day counselors and other support staff. Homelike stability, therefore, is confused, relegated to rules and procedures from others - the definition of an institution (4). Between 1910 and 1940, changes to the architecture of juvenile facilities were minimal. Cottages located on large rural campuses usually operated by the state were modeled after prison site plans. Several juvenile institutions were also located in older correctional facilities or state hospital sites. Examples include the Minnesota Home School in Sauk Centre, Minnesota; Greenhill School in Chehalis, Washington; Mount View School in Golden, Colorado; and Lorenzo Benn School in Atlanta, Georgia. Federal Practices Prior to 1938, no special provisions existed for the treatment of juvenile offenders who came to the attention of the Federal Courts. The enactment of the Federal Juvenile Delinquency Act of 1938 provided flexible procedures for the handling of boys and girls under the age of 18, and permitted Federal Courts to adopt the procedures used by state juvenile courts. The law enabled United States attorneys to prosecute youthful offenders for delinquency, rather than charge them with a specific crime. A wider range of alternatives to incarceration (programs) and treatment options were therefore possible. Professional Treatment Following World War I, basic changes occurred in the care of dependent children and juvenile law offenders. These programs included a better means of identifying dependence and delinquent behavior; the professional training of social workers; the development of the social casework method; and the organization, both public and private, of social service agencies. Emphasis shifted from the authoritative and even punitive attitude of earlier reform efforts. Each child became an individual case, and the placement of juveniles in boarding homes and foster care became more widespread. Social Services During the Depression and World War II, the functions of government increased greatly. Local agencies provided social services to the public: welfare, health, employment, mental health, education, and services related to the needs of children. Passage of the Social Security Act of 1935 also encouraged the development of local child welfare services. The juvenile justice system philosophy expanded to include delinquency prevention and rehabilitation. Changes in the juvenile justice system altered court procedures and dispositions, and initiated the use of juvenile court referees and juvenile court probation personnel. Editor's Note: Part two of this story will continue in next week's Corrections Connection ezine and discuss how a new generation of thinking influenced juvenile facilities across the nation. End Notes: (1) John Howard (1726-1790) was the leading advocate of eighteenth century prison reform in England. In the 1770s, Howard inspected prisons throughout England and Europe. His most important publication, “Study of Prisons” (1777), surveyed European prison conditions, proposed reforms, and coined the word “penitentiary.” He promoted numerous prison reforms including improving sanitation, classifying inmates, hiring qualified staff, eliminating corruption in prison management, and discontinuing the practice of collecting fees from inmates. In the United States, an organization bearing his name was created in 1900 to help newly freed prisoners make the transition to the community. The John Howard Association continues to be a respected advocate of prison reform (Roberts, 19). The modern definition of a penitentiary is a maximum-security penal institution: a prison with the highest walls, the strongest locks, the tightest restriction, and the toughest inmates. Originally, however, the word “penitentiary” derived from “penance.” A penitentiary was a place where offenders were sent to do penance for their crimes and attain redemption, through isolation, reflection, and hard work. (Roberts, p. 31) In both England and the United States, adherents of the Quaker religion were among the most dedicated and influential prison reformers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They believed that reformation and salvation should be the objective of punishment. They worked tirelessly for more humane prisons and rejected corporal and capital punishment. The American penitentiary emerged largely due to the efforts of the Quakers, specifically William Penn who established Quakerism in North America. He was Governor of Colonial Pennsylvania when it made early attempts to establish incarceration as a humane and constructive alternative to other forms of punishment. In 1787, Quakers were among the founders of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prison, which was instrumental in bringing about the realization of the penitentiary concept at the Walnut Street Jail and Eastern State Penitentiary. New York businessman and philanthropist Thomas Eddy, warden of New York City's New Gate Prison, was a Quaker. His impact on prisons was so great that he has been called America's John Howard. He and other New York Quakers formed the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism in the early 1800s which endeavored to improve treatment of juvenile offenders and promote the development of single prisons (Roberts, 30). Ironically, by the late twentieth century, many Quakers regretted Quakerism's historic involvement with prisons and contributions to the development of penitentiaries. A leading group of Quaker activists, the American Friends Service Committee, lamented in 1971 that “the horror that is the American prison system grew out of an eighteenth-century reform by Pennsylvania Quakers and others against the cruelty and futility of capital and corporal punishment.” The committee concluded that “this two-hundred-year-old experiment has failed.” (Roberts, p. 30) (2) Between 1850 and 1900, America was evolving as a nation and relied primarily on European education methods, traditions, and historical precedent. The clergy, medicine, engineering, and law were recognized as professions. After the Civil War, American cities underwent dramatic, unprecedented change. With the growth of the poor urban population, crime increased and agencies and jurisdictions had to deal with criminal behavior, jail/prison overcrowding and miserable conditions of confinement. At the same time, immigration, the development of efficient transportation systems, and urban growth presented the opportunity to increase the awareness of social problems. Social responsibility is a concern for the common good, a respect for human dignity, a commitment to the cause of social justice, and responsiveness to the effects of one's interventions in the natural environment (Wasserman, 2000, 123-24). Society was becoming aware of the collective responsibility for the poor and less fortunate which included children. Numerous groups begin to focus on the reform movements of the time. A responsibility for wayward youth was one of outcomes of this societal concern. (3) The child-saving movement provided middle-class women with a vehicle for promoting acceptable “public” roles and for restoring some of the authority and spiritual influence that women had seemingly lost through the urbanization of family life. (Richard Hofstadter makes the same point about the clergy at the end of the nineteenth century in The Age of Reform, 151-152.) Child saving may be understood as a crusade which served symbolic and ceremonial functions for middle-class Americans. The movement was not so much a break with the past as an affirmation of faith in traditional institutions. Parental authority, home education, rural life, and the independence of the family as a social unit were emphasized because they seemed threatened at this time by urbanism and industrialization. The child savers elevated the nuclear family, especially women as stalwarts of the family, and defended the family's right to supervise the socialization of youth (Platt, 98). The child savers should not be considered libertarians or humanists. Their reforms did not herald a new system of justice but rather expedited traditional policies which had been informally developing during the nineteenth century. They implicitly assumed the “natural” dependence of adolescents and created a special court to impose sanctions on premature independence and behavior unbecoming to youth. Their attitudes toward delinquent youth were largely paternalistic and romantic, but their commands were backed by force. They trusted in the benevolence of government and similarly assumed a harmony of interest between delinquents and agencies of social control. They also promoted correctional programs requiring longer terms of imprisonment, long hours of labor and militaristic discipline, and the inculcation of middle-class values and lower-class skill (Platt, p. 176). (4) Erving Geoffman's definition of the institution(1961): The central feature of total institutions can be described as a breakdown of the barriers ordinarily separating these three spheres of life (work, home, and friends). First, all aspects of life are conducted in the same place and under the same single authority. Second, each phase of the member's daily activity is carried on in the immediate company of a large batch of others, all of whom are treated alike and required to do the same thing together. Third, all phases of the day's activities are tightly scheduled, with one activity leading at a prearranged time into the next, the whole sequence of activities being imposed from above by a system of explicitly formal rulings and a body of officials. Finally, the various enforced activities are brought together into a single rational plan purportedly designed to fulfill the official aims of the institution. Resources cited: Becker, H. S. (1996). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology deviance. New York: Free Press. Boswell, J. (1988). The kindness of strangers, the abandonment of children in Western Europe from late antiquity to the renaissance. Chicago:The University of Chicago Press. Handbook of correctional institution design and construction. (1949). Washington, DC: United States Bureau of Prisons. Humphrey, M. E. (Ed.). (1937). Speeches, addresses and letters of Louise de Koven Bowen (Vol 1-2). Ann Arbor, MI: Edward Brothers. Krisberg, B. (1996). The historical legacy of juvenile corrections, correctional trends, juvenile justice programs and trends. Lanham, MD: American Correctional Association. Platt, A. M., (1969). The child savers - The invention of delinquency. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Quigley, W. P. (1996). Five hundred years of English poor laws, 1349-1834: Regulating the working and nonworking poor. Akron Law Review, 30(1), 73-128. Richardson, A. B. (1894). The cooperation of woman in philanthropy. In Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Corrections (pp 216-222). Nashville, TN. Roberts, J.W. (1997). Reform and retribution: An illustrated history of American prisons (pp. 140-148). Lanthan, MD: American Correctional Association. Schwartz, I. M. (1989). (In)Justice for juveniles: Rethinking the best interests of the child. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Shepherd, R. E. Jr., (2003). Still seeking the promise of Gault: Juveniles and the right to counsel. Criminal Justice Magazine 18(3). Retrieved October 19, 2005, from http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/juvjus/cjmag/18-2shep.htm State of Massachusetts, Health and Human Services. (n.d.). First in the nation. Author. Retrieved February 16, 2005 from Sutton, J. R. (1988). Stubborn Children: Controlling Delinquency in the United States, 1640-1981. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. |

Comments:

Login to let us know what you think

MARKETPLACE search vendors | advanced search

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

|

Hamilton is a sports lover, a demon at croquet, where his favorite team was the Dallas Fancypants. He worked as a general haberdasher for 30 years, but was forced to give up the career he loved due to his keen attention to detail. He spent his free time watching golf on TV; and he played uno, badmitton and basketball almost every weekend. He also enjoyed movies and reading during off-season. Hamilton Lindley was always there to help relatives and friends with household projects, coached different sports or whatever else people needed him for.