|

|

| Simple place for a simple man |

| By Ann Coppola, News Reporter |

| Published: 11/05/2007 |

The nondescript setting that is Point Lookout Cemetery seems fitting for those who rest here. Austere columns support a wired arch above its entrance that holds the word “cemetery” in large white letters. They match the stark, cross-shaped grave markers, which tell nothing of those buried beneath them. Perhaps there is no story to be told for the dead here, but for Louisiana State Penitentiary inmates this facility's cemetery still serves as a symbol of dignity.

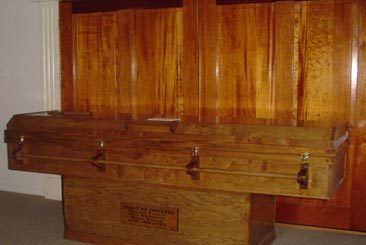

The nondescript setting that is Point Lookout Cemetery seems fitting for those who rest here. Austere columns support a wired arch above its entrance that holds the word “cemetery” in large white letters. They match the stark, cross-shaped grave markers, which tell nothing of those buried beneath them. Perhaps there is no story to be told for the dead here, but for Louisiana State Penitentiary inmates this facility's cemetery still serves as a symbol of dignity.Of Angola’s 5,000 inmates, 90 percent are expected to die in prison because of their life sentences. For a time, those who died and were unclaimed by family were handled rather unceremoniously. When Warden Burl Cain arrived at the facility he sought to change that through a program that would instill more respect for the dead and create a sense of dignity for those still alive. “The coffin building started because we were using cardboard coffins just prior to me being warden back in 1995,” explains Cain. “It was real primitive. They just dug the graves with a backhoe and no one really came to the funerals. I told the inmates, ‘This is your home, it’s where you live. You should be building these coffins.’”  Building a casket The inmates agreed, and a small group of them began building birch plywood caskets. Also around this time, Angola graduated its first inmate preachers through a bible college program run by Louisiana State University. “We decided to build a horse drawn carriage and pull the coffins to the cemetery. We thought we’d have a real fancy funeral and the inmates could preach it,” he adds. The new ceremonies generated immense feelings of pride among the inmates. “They were really proud of it,” Cain says. “They said, ‘Princess Di and JFK were carried in a horse drawn hearse.’ We gave a lot of dignity to it. The inmates didn’t really mind that they were going to be buried here anymore.”  Over the years, there have only been two or three coffin-builders at a time, but, according to Cain, “they always stay three ahead”. “We have about a funeral a month here. It takes them about two or three days to build one. We get a comforter from Wal-Mart for the inside, and that’s how it’s done.” In 2005, the modest coffins received some high profile attention. Preacher Billy Graham’s son, Franklin Graham, visited Angola to preach that spring. He then stopped by the Louisiana State Penitentiary Museum and made an unexpected request. “He went to the museum where we have a coffin on display,” explains Cain. “He asked how he could get two of them. He wanted one for his mom and one for his dad.” The coffin-builders at the time, Eugene Redwine and Richard “Grasshopper” Leggitt stepped up to the task. “Grasshopper said to Franklin, ‘Well it’s a simple coffin for a simple man with a simple message,’” Cain recalls. “I asked Franklin if he wanted a fancier plywood, like ash. He said they wanted them exactly like the inmates'.” Ruth Bell Graham, Billy Graham’s wife passed away on June 14 this year. Pictures from the funeral service on the Billy Graham website show Redwine and Leggitt’s casket covered with white flowers and red roses by each of the preacher’s five children.  “People were really proud to think they would be buried like the Grahams,” adds Cain. “Grasshopper said it was the greatest honor in his life to build for the family. For a prisoner to say that, it really had a calming effect on the prison.” The coffins have done more than just transform the way an inmate’s death is handled. They’ve contributed to a facility-wide cultural change. “In our business, when an inmate starts giving back and starts being unselfish. That’s the first sign of being rehabilitated,” he says. When he became Warden, Cain says, about 400 inmate-on-inmate acts of violence were committed each year. That number has dropped to between 70 or 80 conflicts in the last two years. He also claims Alabama’s recidivism rate for 2007 has dropped to about 39 percent.  The finished product Cain attributes this success to promoting moral themes. “I don’t preach religion, I just talk about morality,” he explains. “I had to get the inmates here to change themselves by convincing them to be their brother’s keeper. Even if I were an atheist, I’d still realize moral people don’t rape, kill, or steal.” Angola won’t be looking to compete with the private coffin-making business anytime soon, but the program continues to be a powerful symbol for a community that now strives to lookout for their brothers, including the ones that have passed on. Related Resources: More about Point Lookout Cemetery |

Comments:

Login to let us know what you think

MARKETPLACE search vendors | advanced search

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

|

Always good content... Sin City Stucco of North Las Vegas

i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.i will tell you later.

It is obvious to anyone who has met Burl Cain that he leads Anglo with his heart. It is evidenced by the coffin program and countless other programs he has intiated that have great meaning for inmates. Not everyone in positions of responsibility thinks in that way. Burl is unique.

This was such a good article. Well told and written. We need to read more about affirmative things taking place, encouraging us that our work is not wasted time and energy, that dedication to this correctional work makes a difference somewhere. Lead on.