|

|

| Please (don’t) recycle |

| By Ann Coppola, News Reporter |

| Published: 04/14/2008 |

With more than one in every 100 adults in a United States jail or prison, there are now millions of children across the country with at least one incarcerated parent. This puts these children at greater risk for a number of emotional, behavioral and psychological problems, including depression, poor academic achievement, criminal behavior, and incarceration. But perhaps the greatest obstacle they face is the overall lack of adults who are talking about how to help them.

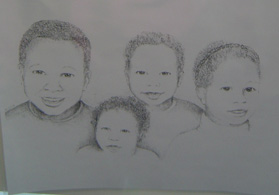

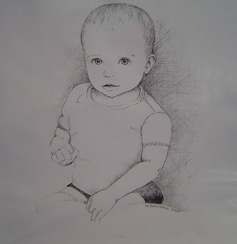

With more than one in every 100 adults in a United States jail or prison, there are now millions of children across the country with at least one incarcerated parent. This puts these children at greater risk for a number of emotional, behavioral and psychological problems, including depression, poor academic achievement, criminal behavior, and incarceration. But perhaps the greatest obstacle they face is the overall lack of adults who are talking about how to help them.Last week, a one-day conference at Bryant University in Smithfield, Rhode Island aimed to initiate a dialogue on how to bring this unique population to the front of the nation’s consciousness. Interrupted Life: A Conversation About the Children of Incarcerated Parents drew a crowd of 160 attendees, including local community leaders, social workers, probation officers, day care providers, teachers, children’s advocates, and formerly incarcerated parents. “Today’s conference is about the children,” began Roberta Richman, assistant director of Rehabilitative Services for the Rhode Island Department of Corrections (RIDOC), one of the eight conference sponsors. “There is no more poignant scene than seeing a group of small children lined up in front of a prison’s gates, waiting to go through security to see their mom or dad.” In the morning’s keynote address, Providence Mayor David Cicilline spoke of his frequent interactions with these kids. On September 30, 2007, of the 3,072 children of incarcerated parents in the state, 1,300 resided in Providence. “I was visiting a fifth grade classroom one day and saw a boy in the back that looked upset and was not participating,” Cicilline said. “When I asked him what was wrong, he told me his mother went to jail five days ago. And yet we expect him to be in school, be on time, and pay attention. What about the trauma from the day of the arrest? What experiences has he had since then?” Elizabeth Burke-Bryant, executive director of Rhode Island KIDS COUNT, moderated the panel discussion that followed. KIDS COUNT is a national and state effort to track the status of children in the United States. It is the only chapter in the country that has made significant gains in collecting data concerning children of incarcerated parents. “These are hidden children,” Burke-Bryant said. “We need to start counting them. As far as the number of kids we need to do better for, 3,027 seems like a doable number. In Illinois, it’s a very different conversation, but Rhode Island is like a laboratory. If we can figure it out in Rhode Island, which has similar demographics in its cities as other major cities, then we can become a model for the nation.” “Not only is this a doable number, but look at how many of these kids are located near each other,” agreed panelist Elizabeth Roberts, the state’s Lieutenant Governor. “They live in the same neighborhoods and communities. Two-thirds of children with incarcerated parents are in our core cities. We’re working with a relatively small number of school systems here.” Panelist and RIDOC director A.T. Wall explained what services his department currently offers for the children of its inmates. “Parenting programs are now not just in the women’s facilities, but are also available for men at the minimum and medium facilities,” Wall explained. “We looked at our security practices during phone calls and visits to make them more family friendly. We’re also working with the state child support enforcement unit to develop plans to foster connections with the families.” Even with the substantial improvements, Wall expressed a desire for much more to be done. “Transitional services is an area where I think we need to do better,” he said. “I’d like to see the day where part of our discharge planning brings the family to the table prior to release. We should acknowledge that the family is going to be the first line of defense and is going to face a tremendous amount of stress upon that parent’s release.” “Our goal is to understand what is going on in the hearts and minds of the child and parent, and what it means to be a child walking though a prison gate waiting to be searched,” added panelist Patricia Martinez, director of the Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF). Its caseload currently consists of 313 children who have a parent incarcerated. “We want to break the cycle of intergenerational crime,” Martinez added. “I have heard of so many caseloads managing 18-year-olds who had a parent incarcerated at some point in their young life. That’s what we’ve done as a system. We have recycled families.” Martinez’s point drew shouts of applause from the audience. The conference’s final speaker, Joyce Dixson-Haskett, a Michigan-based advocate for children of offenders, presented her Levels of Response to Traumatic Events (LORTE) model. LORTE is a curriculum to be used in designing programs for children of incarcerated parents. A formerly incarcerated mother, Dixson-Haskett also shared her own personal experience. “I was prepared to go to prison for what I had done,” she said. “I was not prepared for what it would do to my children. My children were ostracized and branded in the community.” “I received a natural life sentence, and they told my children to treat me like I was dead,” Dixson-Haskett said, breaking into tears at the podium. That experience, she explained, demonstrated to her that most adults do not know how to interact with children of offenders. The LORTE model maps out the emotional trauma and behavioral manifestations that are specific to children with incarcerated parents. “It is my ultimate desire to give all caregivers, grandparents, foster care workers, judges, teachers, and case workers a model to follow,” Dixson-Haskett concluded. “Children don’t fall through the cracks, they slip through fingers. Fingers that would do more, but have too big a caseload. Fingers that would do more, but have too little money. This is not a segmented problem, this is a national problem. We need deep pockets, policy makers, public health, everybody to get behind this.” The speech received a standing ovation. Before wrapping up, the conference broke into three workshops. Three different panels addressed institutional programs, transitional services, and community-based programs, giving audience members the chance to ask questions and present their own opinions and experiences. “This conference, for me, I feel redeemed, especially for the children that didn’t have a voice,” said attendee John Prince, an outreach specialist for Rhode Island’s Family Life Center. The center provides case management services organization for ex-offenders and their families. “This arena has given people the chance to understand the kids,” he added. “This is a way to give these kids that are under so much scrutiny some hope that there will be someone to listen to them.” “I was struck when Patricia [Martinez] talked about the recycling of families,” Wall reflected. “The topic of children of incarcerated families is really about making an investment. If we can’t make it now, we’re doomed to recycle future generations.” The conference also had on display portraits of incarcerated mothers’ children, sketched by an inmate at RIDOC’s prison for women. The children’s faces looked on from the back of the conference hall, smiling as if they had heard every word.    Related Resources: Resources from KIDS COUNT More on DCYF More on the Family Life Center |

MARKETPLACE search vendors | advanced search

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

|

Comments:

No comments have been posted for this article.

Login to let us know what you think