|

|

| The Way Back Home: Arrested Development and War Veterans Return to Civil Society |

| By Berkeley Harris, MSW |

| Published: 11/09/2009 |

Editors note: Berkeley Harris, program manager of Families in Transition Community Services continues his series "The Way Back Home".

Editors note: Berkeley Harris, program manager of Families in Transition Community Services continues his series "The Way Back Home".

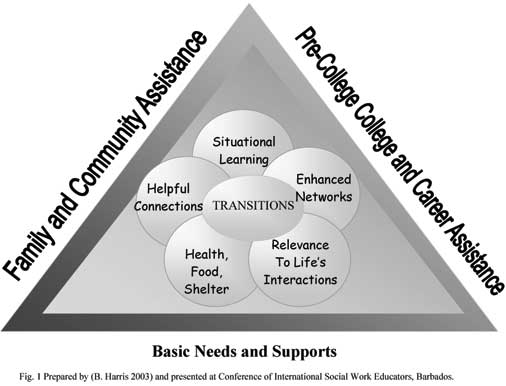

“ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT” AND THE CHALLENGE OF WAR VETERANS’ REENTRY TO CIVIL SOCIETY This document offers a framework that describes some key components that Veterans Associations/Agencies must address to reduce and ultimately eliminate disparities in servicing returning veterans to civil society. While the framework is not prescriptive in nature, it identifies eight principles to guide action, that if addressed in policy, practice, programming and training are likely to bring about positive change. These expressed principles are harnessed in the following diagram. “From Research to Results”  The model addresses the inclusivity necessary in the world of Veterans Resocialization to Civil Society. We cannot reintegrate in a box of seclusion. When a veteran of war returns to civil society, he or she has to readjust to environmental conditions far removed from those of a war-zone. More often than not, family members, her civil peers, may have left her behind academically, socially and spiritually. The consequences of war may continue to haunt the veteran, and a “sense of loss,” may well be present, but ignored. One may ask the question, “How can you have a sense of loss from being on the front-line?” The question may also be asked, “Why do so many want to return to the front-line?” Is it that euphoric? Or is it that they so much want to “serve their country?” Such transitions can only create a detachment so intense to family and community, that the veteran may well see herself/himself as an outcast. Any understanding of this “Lossness,” may well translate itself into what William Bridges (1991) describes as the Neutral Zone.: A time of “Lossness,” anger, or disequilibrium, a time of redefining one’s role in society; A time of non-recognition by the political administration for whom the veteran so valiantly lost a limb. Such elements of grief and loss may well be under-currents to unusual behaviors exhibited by the veteran, which may be referenced to loss of loved ones at home in civil society or close knit relationships on the front lines of the war-zone.. In an interview with a recent veteran and his fiancée, during an intermission of one of my ‘Change Management Classes’ at a California Community College; the fiancée approached me with her Vet by her side. He had three months returned home from Iraq, having sustained a neck injury. Her concern was, he was almost afraid to go job hunting, and was staying in the house on a daily basis, even though he felt better and had the desire to work in civilian settings. He confessed that though he had the desire to work, working in a civilian setting was a fearful proposition. That’s why he had come to the class, so that he would hopefully find some solutions. This is one of many stories from war veterans, and their losses. Even their former social settings of family and community may seem foreign to them upon their transition from a war-zone. Confronting these circumstances, it is not surprising that many young veterans choose to return to the war zone over school and civil society, thereby foreclosing a major opportunity for improving their lives, More than sixty percent of veterans need a College education to compete in today’s civil society. Former or present warriors, because of their aggressive war record, may easily face alienation. Persons fearing guilt by association may believe that associating with a known veteran or a soldier of the front line may imply to others that they too have aggressive or warlike tendencies upon their return from the war zone,and if stable sources of support refuse to assist them, this rejection may exacerbate the mental, physical and psychological hardships experienced by the veteran. Arrested development, coupled with social isolation and/or alienation that this type of treatment exhibited by civil society and other people may well create a key risk factor for deviant behavior and psychopathology. In personal interviews with veterans experiencing this kind of trauma and/or alienation, many feel that it is undeserved. These individuals feel that they have served their country well, have paid up a debt on their responsibility to society, and therefore require of the country a holistic reentry process, and need to be treated as citizens of worth. Considering the concept of “arrested development;” It should be kept in mind that many of the social factors important in a teenager's life still have some relevance in the lives of particularly, males in their twenties. In the civil world, a large portion of a teenager's life is spent at school. During an average school day a teenager may spend six to seven hours on school grounds. Many or most of the teenager's social interactions directly involve the school environment. Militarism deprives youth of this civil environment, and while serving a military environment, they miss out on these interactions that influence the development of their school-aged peers outside the armed forces. While their counterparts are developing and adapting socially and psychologically to the environment of civil society; Youth in military training, usually poverty-stricken youths, have greater social and psychological gaps. Many combat personnel are highly dependent on their families, friends, or military resources and are compelled to develop in ways adaptive mainly to the preparation for war environments. They need to have easy access to civil assistance at reentry. Strong civil reintegration training, and “change management” processes can only enhance smoother “transitions” processes. Grief and loss issues also need to be elevated in the reentry training process. . Depending on the length of military time served and the type of experiences a person has had while in combat, they may have little ability to resist reverting to the behaviors learned for war. Also proofs of disabilities or radical impact on their lives need to be addressed in an enhanced culture of understanding new warfare fall-out. A “holistic approach”: as outlined in the above diagram has been developed to demonstrate the process of providing steps to more effective awareness and resources to accommodate the veterans’ reentry process into a new and civil society: Such pathways, while not the end all, may include the following approaches: Family and Community assistance are critical to the reentry process to civil society. Most veterans interviewed reported that, they depend heavily on family cohesion and acceptance on return, more so than anything else. However, their behavior has serious impact on family reunification. A community is usually out of touch with the veteran’s realities, and consequently misunderstands the resocialization process. “Community development” if used in understanding “arrested development” should be a training opportunity for all. Pre-college, college and Career assistance can only enhance opportunities for veterans to reclaim their civil place in society for the common good. Post-secondary education has become the hallmark in present-day competitive work environments. Not to provide this opportunity in a personal, and on an individual basis, can only exacerbate the already questionable matter of veteran resocialization. Basic needs are an essential part of the reentry process. When on the battle field, these are readily supplied. In his dissertation on the hierarchy of needs, Abraham Maslow advances the argument that food, shelter and clothing are essential features to the beginning of well being, and that one will find it very difficult to engage in relevant abstract processes, if these basic needs are unmet in the individual’s life. It is not unusual for veterans to become homeless, often before, or on return to civil communities, consequently resorting to illicitly medicate themselves to ease their discomfort, shame, pennilessness and pain in their “arrested development” phase. Society on a whole has an obligation in providing services. However, Their Commander in Chief should be held responsible for a successful or enhanced reentry process. Once a veteran always a veteran! There should only be inclusivity in this process, and the only way to achieving this process is the “Holistic Way.” The pathways outlined and possibly utilized in Fig. 1 can be a start to recover pride in our gallant men and women, our veterans Berkeley Harris is a program manager of Families in Transition Community Services Inc., an organization that provides technical assistance to youth-based educational mentoring programs for Youth of Incarcerated Parents; Offender ReentryTheory and Practice;21st century emotional intelligence skills for Foster Youth and Caregivers; Transitions Management training, workshops for adult and seniors' transitions, and project evaluation. Berkeley's presentations span the Caribbean, Africa and North America.He has worked in Corrections as a Probation/Parole Officer and has also through the Solicitor General Office, led a team to train and develop Ontario Police Services, Canada, in Police Community Development. He's a recipient of many International awards for his vision and innovation. Other articles in this series by Harris: |

MARKETPLACE search vendors | advanced search

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

|

Comments:

No comments have been posted for this article.

Login to let us know what you think